The month of February is known as Black History Month, and what better way to celebrate than to relish in the imagery created by black women photographers? I suppose, seeing the work in person would be better tenfold, but for now, let these photographs settle into your sights.

A big part of my search for these women was part recollection: whose work have I already come to know and love? I wrote eight names down. The second half of my search was uncovering the 1985 book, Viewfinders: Black Women Photographers, written by Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe. The book is described as a bible of sorts to some black women creatives, as it is a collection of diverse photographs from black female photographers from the mid-1800s to the late 1980s. An introduction to Viewfinders lead me to an important article by Vogue, which presented a new book that took on where Moutoussamy-Ashe left off.

Mfon: Women Photographers of the African Diaspora was created some 30 years later by two Brooklyn born photographers, Laylah Amatullah Barryn and Adama Delphine Fawundu. Barryn and Fawundu have come together to preserve and document the work of more than 100 women photographers of African descent from around the world.

I highly suggest picking up Mfon, and visiting your local library to pick up Viewfinders, or snagging it on Amazon. But first, enjoy the works by these 16 women photographers below, and truly allow them to make space for what you don’t often see in the world of Western eyes. Don’t scroll past! Put a timer for 5 minutes for each photo if you must. Have some control over what you’re digesting, and really let these works sink in:

Michelle Agins

Michelle Agins, is one of the longest-running staff photographers at The New York Times. She has worked since June 1989 as a staff photographer with the NY Times, and has been documenting life in major cities like New York, Chicago, and Baltimore as a journalist since the 1970s.

Agins first got her start as an intern for The Chicago Daily News and in less than a year became a sports photographer. In 2001 Ms. Agins and her colleagues won a Pultizer Prize for National Reporting on the series How Race is Lived in America.

In her famed photo of James Baldwin, the novelist introduces his new Book “Evidence of Things Not Seen” at the Home of Lerone Bennett in Chicago in 1983, Agins captures the writer, host and friends conversing round a kitchen table. A pack of cigarettes and a lighter, glasses and plates, all dictate the mood of what otherwise might be a leisurely conversation. Yet Agins places herself just above the table, to show us how well she can record the moment without breaking the intensity of Baldwin’s sightline.

Carrie Mae Weems

Carrie Mae Weems is one of the most noted black women photographers in art history. Her 1990 photographical series Kitchen Scenes was inspired in part by the influential essay “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” (1975) by the critic Laura Mulvey, which addressed the lack of non-objectified representations of women in film and other cultural expressions. As such, Weems offers a valid portrait of an often overlooked subject, in this case, a modern black woman.

Weems’ gelatin silver prints trace a period in the woman’s life as she experiences the blossoming, then loss, of love, the responsibilities of motherhood, and the desire to be an engaged and contributing member of her community.

Lorna Simpson

Lorna Simpson is an American conceptual artist whose works deal with identity politics as a black woman. In her piece, Five Day Forecast, Simpson combines image and text to examine the processes through which meaning and understanding takes place. In these early works Simpson often used the image of a black woman, photographed cropped, or from behind, against a stark background, and accompanied by text panels. Both text and image are deliberately austere in style. Five Day Forecast was first conceived in 1988, at which time Simpson made two versions of the work using Polaroid photographs; one of these was subsequently damaged. In 1991 she decided to remake the work in an edition with silver gelatin print photographs which she shot with a large format 5 x 4 camera.

The words, with their negative connotations, imply a repeated breakdown in communication, within personal, professional and racial relationships. At the same time, the pun on ‘mis/miss’ raises questions of gender and identity and the exchange of power within such relationships.

Deana Lawson

You’ll probably recognize Deana Lawson’s striking work as the cover of musician Blood Orange’s third released album, Freetown Sound. Lawson’s photographs are erotic in nature, and at times intimate, conjuring thoughts of mortality, motherhood, and protection.

What I love most about Lawson’s way of seeing is her approach to her subjects. Taking to the everyday aspects of life, Lawson engages with her subjects in subways, grocery stores, and out on the streets location scouting. In a conversation with esteemed photographer Catherine Opie, Lawson answered how she chose the subjects in her photograph, The Garden. En route to a field of grass, Lawson asked a woman and a man if they would pose for her. The two, strangers at first, sit in the grass where we gaze upon a moment of tenderness we would presume belongs to a loving couple with child.

No matter how bare fleshed her subjects can be, and no matter how much appreciation we can take from the human form, the image and the moment is for the subject and photographer alone. That is something I always try to digest when I view Lawson’s work, and it blows my mind every time. Just when imagination takes hold, the truth in the photograph reveals a mutual respect, trust, honesty, and above all, representation.

“As a Black African woman I’ve struggled with my identity and the oppression of my hair in a European Country. I want to show girls who are in the same situation that our hair is beautiful no matter the shape, colour or texture,” says Bela.

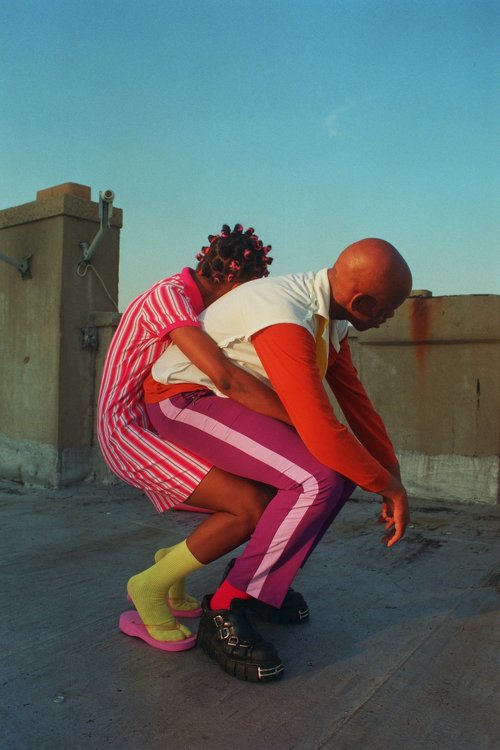

Oriana Koren

Oriana Koren is an editorial photographer and writer based in Los Angeles, CA whose work is anchored in food, culture, and travel. Interested in the intersections of food, history and community, Koren’s work is a fusion of personal narrative and in-depth documentary practice focusing on the principal contributions of people of color, immigrant, and womxn’s communities within American foodways and food culture.

Molding narrative and documentary, Koren develops a blend of beautiful portraits in her commissioned piece, Underground Chefs. Koren focuses her lens on the home cooks like Chyna Pace (photographed above) of South LA who transform their homes into a place of business, where they can build on their craft to feed their passions and communities, all while making a name for themselves.

Koren is part of PDN’s One’s to Watch, and her clients include The New York Times, and Washington Post. Feel free to watch this wonderful video of Koren on “Breaking the Barriers to Success” which provides major insight on how to make it as a woman of color in the editorial industry.

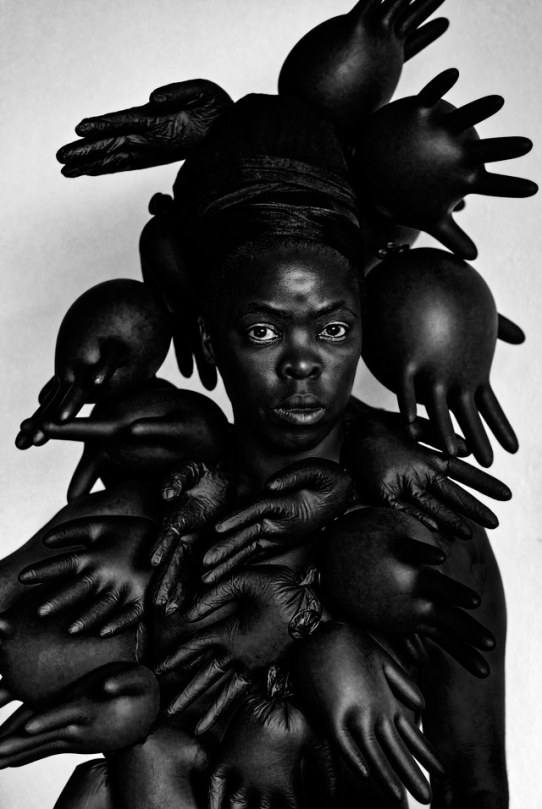

Samantha Box

Samantha Box is a documentary photographer based in Brooklyn, New York. Since 2005, she has documented New York City’s community of LGBTQ youth of color, the social issues affecting these young adults, and the structures of family, intimacy and validation that bind and protect them. The resulting body of work, INVISIBLE, is a continuing multi-chapter exploration into the lives of this young community.

“The young people that I photograph are some of the most resilient people that I have ever met: despite facing the societal animosity of homo- and transphobia, and the burden of a broken system that conspires to keep them homeless,” she says, “they continuously work for a future where their talents and intellect can be used, where they have a home, a family and a life of stability.”

Her photographs contain strong narrative and documentary elements. Documenting her travels in West Africa, her book about the Gullah community of South Carolina, Daufuskie Island: A Photographic Essay reveals the most intimate black and white portraits of residents of the community. Moutoussamy-Ashe shares her immediate personal experience in Daddy and Me, which features photos of her late husband, Arthur Ashe, and her daughter, Camera living day to day as her father, a well known tennis champion, father, husband and gentleman who died of AIDS in February 1993.